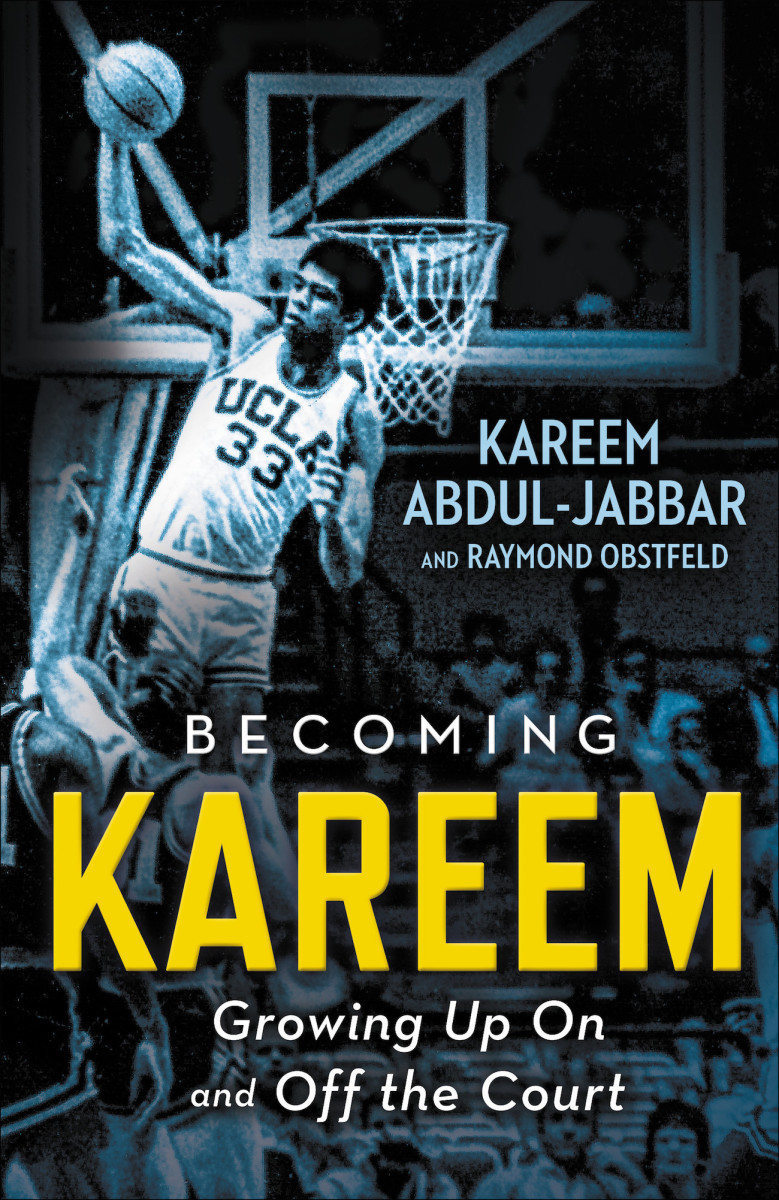

Basketball Legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Has a New Book for Kids

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had 38,387 points, 17,440 rebounds, 5,660 assists, 3,189 blocks, six MVP awards, and five NBA championships in the 1970s and ’80s. These numbers define his career as one of the greatest NBA players of all time, but not the person he is. In his new book, Becoming Kareem, for kids ages 10 and up, Abdul-Jabbar discusses life on and off the court, and what it was like being a tall man in a small world full of hate and discrimination against African-Americans. I spoke with Abdul-Jabbar about his new book and about the challenges he faced growing up.

What was your inspiration for writing this book?

I thought that the things I went through—becoming an adult and going through puberty and figuring out what I wanted to do with my life—were very important parts of who I am. I just figured that maybe I should share it. I wanted to convey what I found out about the process, how you discover who you are, and what you want to do with your life.

How did living in Harlem, New York, as a kid help you to accept and view all people the same?

It was really easy for me to figure out that good people are good people and that it had nothing to do with what they look like. That’s a very important issue because people want [to make a big deal] about race and religion, and those things have very little to do with what's good or bad about a person.

You say that along with the color of your skin, your height made you a target of bullying. Who were the main people who helped you cope with the berating?

My dad told me I needed to learn how to deal with conflict resolution and understand that people might be very committed to bullying because of their fears and things that they don’t want to admit, anything that makes them vulnerable.

Could you elaborate more on how being a model student was both positive and negative for you?

Well, being a model student was a positive for me so far as getting good grades means that you have a future in terms of employment and being able to take care of your own life in a way that you want to. The negative was that [I was] at a school where the other students didn’t have good academic skills or habits, and the fact that I did led them to a lot of resentment [of me] and bullying.

How did having only two other African-American students in elementary school affect your social life?

My school was mainly white, but where I lived there was a good percentage of African-Americans, so I never felt alone. At school I [didn’t have] a lot of African-Americans around me, but at the playgrounds and in the neighborhood it was a different story.

In your book, you talk about the Mikan Drill, which requires a player to shoot continuous layups from either side of the hoop. How did learning the Mikan Drill at a young age help you along your basketball career?

By learning the Mikan Drill, I was able to master more of the techniques for basketball that are very effective, and knowing that technique and being able to execute it at will was something that was really good for me.

What does it feel like knowing that kids are learning about you today, but when you were their age, you were not learning about any famous African-Americans in history class?

I’m glad to see that it has changed somewhat and continues to change, and I hope American heroes of all descriptions are recognized and appreciated.

Did you ever play at Rucker Park, the famous streetball courts in New York City? If so, how did it affect your playing style?

Yes, I did. It really didn’t affect my playing. I basically learned the game through the efforts of my high school coach, so streetball didn’t really have the influence on me.

Knowing that if I did well, better things would happen [for me] pretty soon; that’s an encouraging kind of situation to be in.

You seemed to have a very on-and-off relationship with your high school coach, especially after one of his outbursts during a game in the locker room. How did you get through that time?

It was difficult; it was very difficult. I figured that it was something I had to deal with as long as I wanted to go to college.

How did your experience as a journalist with the Harlem Youth Action Project during the summer of 1964 help you later in life?

It helped me to recognize some things in certain situations in a more mature and responsible way. When you have to report something, it’s a lot more difficult to make mistakes because you [learn to] double-check yourself. It teaches you caution and reliability.

What was the main influence on your decision to go to UCLA?

I think that UCLA really responded to all of the things I wanted; it was a good school and it had a great basketball program. I was confident that UCLA was a very good place for me to go to school.

How did your evasion of the press help your high school and college careers?

Talking to the press was [thought of as] a distraction for coach [John] Wooden, and he didn’t want us to be distracted by all the attention we were getting. That was really what motivated him to keep us from talking to the press all the time.

You grew up as Lew Alcindor and converted to Islam after your second year in the NBA. What was the main backlash from your conversion to Islam?

People would have questions; they were trying to learn what it was all about. At that point, Islam was pretty much under the radar in most American places. Of course that [has] changed, but at that point people just took it as something to try and figure out.

What social event in your lifetime has had the biggest effect on you?

I would have to say the very first one that I became aware of that bothered me, which was the murder of Emmett Till. [In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till, who was African-American, was murdered by two white men.] I would have to say that put me on a long journey to find out what it was all about, so I would have to say that was the most influential.

You met many influential people outside of sports. Looking back, is there one who had the biggest impact on you as a person?

I think that meeting some of my heroes, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Jackie Robinson, and seeing those people and learning from their lives is really what enabled me to be encouraged and do a better job of plotting your way.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Photograph by Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos/Getty Images; cover image courtesy of Little, Brown and Company