An Ode to the Super Bowl, now 50 Years Young

Super Bowl Sunday doesn’t need legislation to become a national holiday — it already is one. If 110 million people are doing the same activity for three hours on a given day, then it’s something special.

This year will be the 50th edition of the great day. And my, how the Super Bowl has changed.

To reach the inaugural game, played after the 1966 season, the Packers and Chiefs each played a 14-game slate. With 12-2 and 11-2-1 ledgers, each won the West division of their respective leagues (then the NFL and AFL). The two teams then went on to capture league titles before going to the “AFL-NFL World Championship,” which was considered second-rate compared to the NFL Championship at the time and was played in front of 32,000 empty seats at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

Now, a half-century later, it’s impossible not to watch the Super Bowl. Or the three rounds of playoffs and two weeks of hype leading up to it. Or the commercials. Or the halftime show. Or virtually anything about America’s Game, which looms larger than life over its main ratings rivals in the sporting world, the NBA Finals, World Series, and College Football Playoff.

Consider this: According to Nielsen TV ratings, the highest-rated college football bowl game of all time is the 2006 Rose Bowl between Texas and USC, seen by 35.6 million people. The lowest rated Super Bowl – the first one in ’67 – drew 39 million viewers. That is how you know your league is big.

But the Puppy Bowl for Humans has given us much more than flashy numbers. On the field, the it has provided some of the greatest moments in the history of sports, not to mention television. Buffalo’s Scott Norwood shanked a potential game-winning field goal wide right, while New England’s Adam Vinatieri sent his right down the middle – twice. San Francisco’s Joe Montana found John Candy and then John Taylor. (The 49ers quarterback pointed out Candy, a famous actor, in the crowd to keep his teammates loose, then led the team on a game-winning march that ended with a TD pass to Taylor.) And Russell Wilson inadvertently found Malcolm Butler last year.

The Guarantee, the Fridge, One Yard Short, the Tiptoe Catch, the Helmet Catch — all in one event, spread through years of history, connecting generations.

There was a time when the NFL played second fiddle to its older collegiate brother, as well as to Major League Baseball. As an example, there was a significant fear when the Cleveland Browns were founded in 1946 that they would not be able to compete in popularity with local college favorites such as John Carroll, Baldwin-Wallace, and Case Western Reserve (all now Division III teams).

The event more responsible than any other for lifting the NFL into its current state in the forefront of the national consciousness is, of course, the Super Bowl. It has done this by taking a championship game and turning it into something much more: an entertainment spectacle with every kind of celebrity, from Coldplay to Colbert. The man who clinched last year’s Super Bowl last year, New England defensive back Malcolm Butler, was only a wee bit more famous than the notorious Left Shark, that wily backup dancer to Katy Perry at halftime that spawned memes galore.

That is what the Super Bowl has become: a generational staple, a cultural phenomenon, a national curiosity. It’s sports’ version of “too big to fail.” While 1994 and 2005 without the World Series and Stanley Cup, respectively, were weird, a year without the Super Bowl would be unholy. It’s so important when a nation, divided along so many lines, can come together over something as simple as a football game.

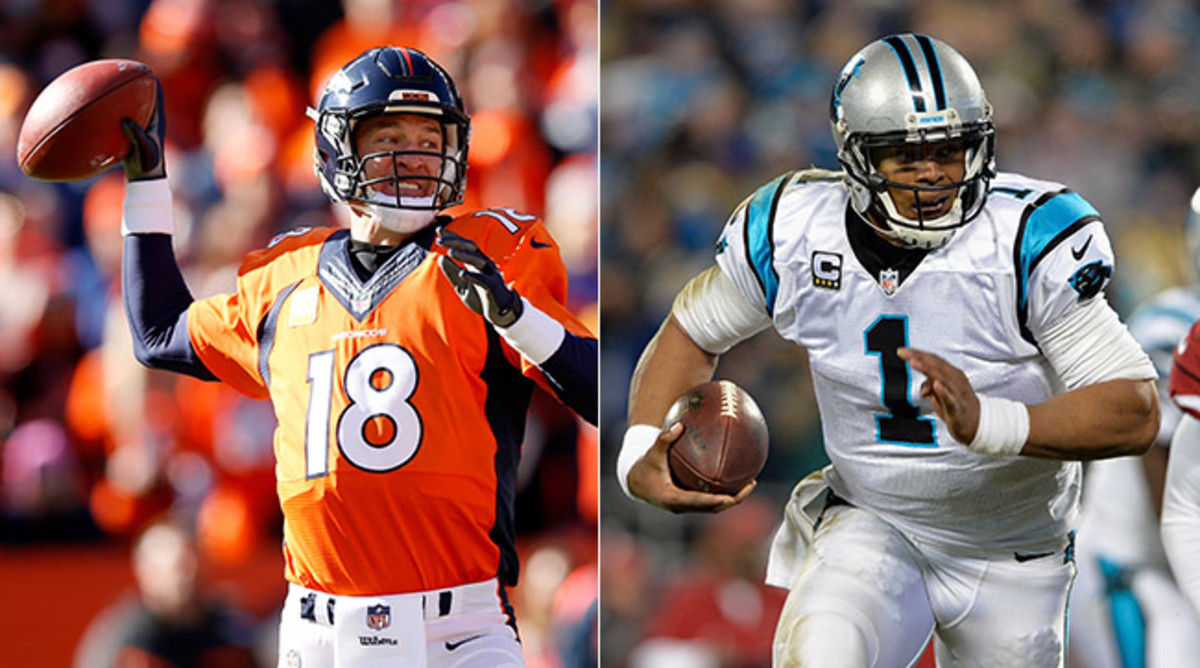

And it is fitting that this 50th Super Bowl will feature its most compelling matchup in years, one beginning and ending at the quarterback position.

Peyton Manning is, in the words of his opposing gunslinger, “The Sheriff.” Manning represents football’s old guard, a product of a bygone era. A traditional passer. A team leader. Soft-spoken and humble. A student of the game, on the brink of retirement.

Cam Newton is the polar opposite: an outspoken, dabbing gridiron improviser who gets things done by any means necessary, by land or air. He represents football’s new school of dynamic, multitalented, larger-than-life celebrity QBs.

The culture clash doesn’t end there. Denver has the best defense in the game; Carolina has the best offense. The Broncos are an aging squad hoping they have one more run in them; the Panthers could be the NFL’s next dynasty, ready to rule the NFC South for years to come.

And this battle of quarterbacking wits will take place on football’s biggest stage, just like previous battles – Montana vs. Anderson, Elway vs. Favre, and Brady vs. Delhomme. Manning and Miller against Cam and Kuechly in NorCal with everything on the line.

We will see history – it’s impossible not to. It’s the Super Bowl, for crying out loud! Let the fun begin.

Photos: Christian Petersen/Getty Images (celebration), Neil Leifer for Sports Illustrated (Super Bowl I), Ezra Shaw/Getty Images (Manning), Grant Halverson/Getty Images (Newton)