Negro Leagues Baseball Museum: An In-Depth Look at Baseball’s Past

Last month, I went to Kansas City, Missouri, to see a Royals playoff game, but I also had another spectacular baseball experience.

My dad and I visited the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. It is located at 18th and Vine streets. During the time when the Negro leagues existed, these streets were the center of life for African-Americans in Kansas City. The people who lived near 18th and Vine, considered the historic jazz district, decided that they wanted to preserve the history of this special place and wanted both the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum there.

The Negro leagues were a collection of African-American teams and leagues. After the Civil War, African-Americans played alongside white athletes, but in 1890 that was outlawed.

There were many different attempts to create a single Negro league; the first successful attempt came from Andrew (Rube) Foster in 1920. He created some teams with a schedule that played each other. Before then, and even after, there were barnstorming teams. (Barnstorming means that they just went all over the country playing any team they could.)

Many Negro leagues thrived from 1920–56, and after that they died out because baseball became an integrated sport in 1947. (Jackie Robinson became the first African-American to play in the majors that year, and others soon followed.)

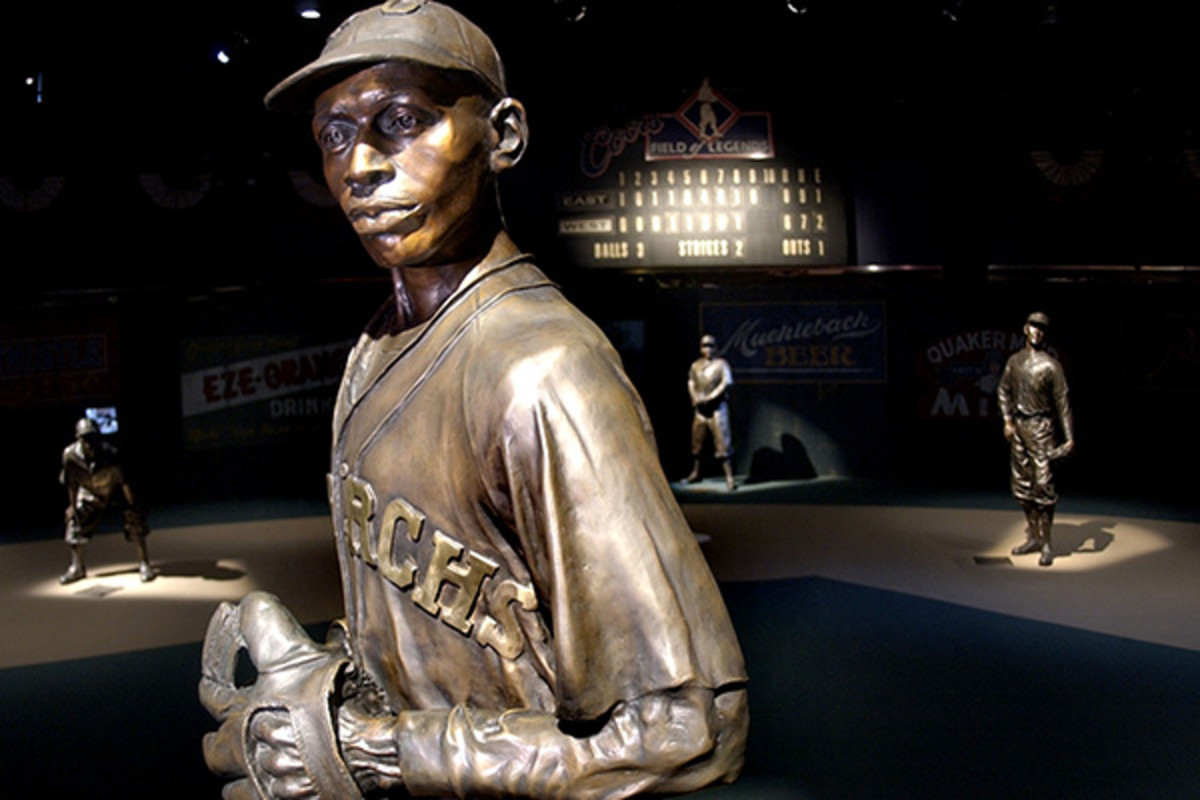

Unlike the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum does not induct players — it honors them all.

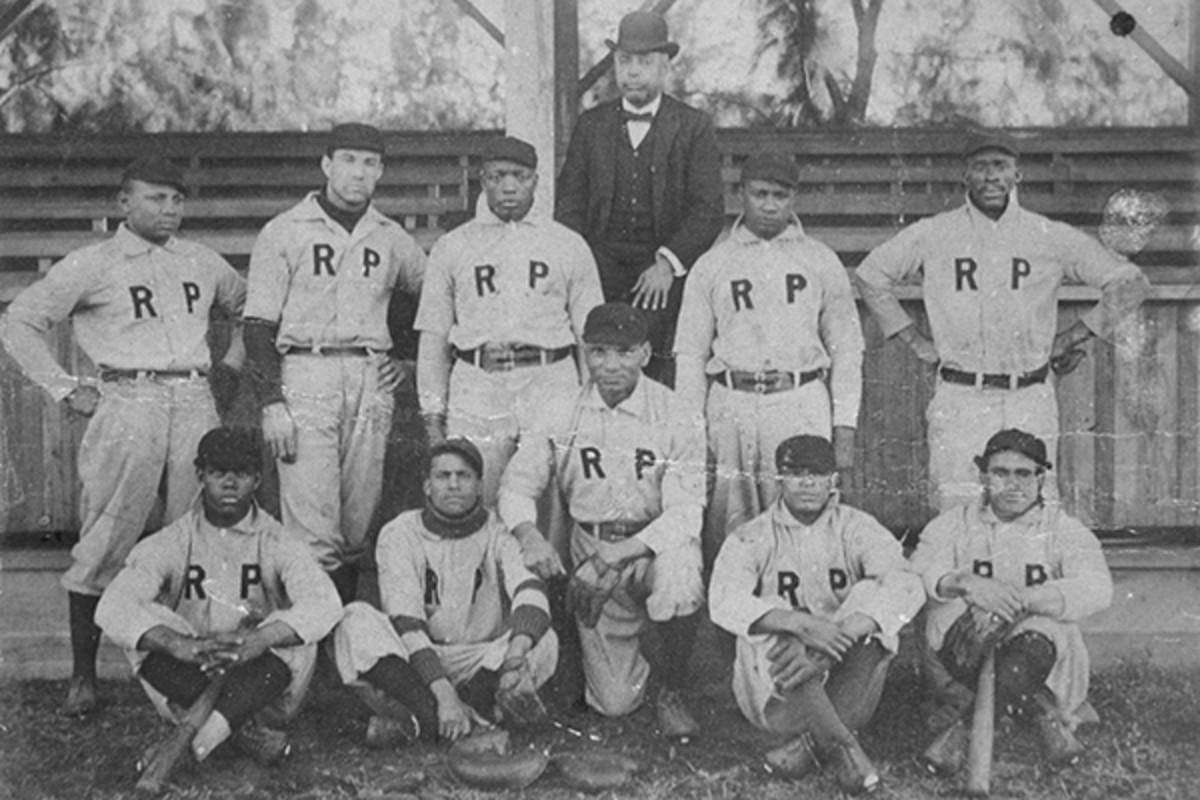

The Royal Ponciana Baseball Club poses near the hotel it represents in Palm Beach, Florida, around 1905. Among the stars of this All-Star team are Sol White, kneeling center, Rube Foster, standing third from left, Home Run Johnson, standing far right, and Emmett Bowman, standing far left.

Examining History

The Negro Leagues Museum has a wide array of artifacts, from uniforms and caps to balls to piggy banks and more. To me, two of the most interesting artifacts at the museum are a newspaper clipping and a baseball.

The museum displays a news story from June 21, 1925, with the headline “Klan and Colored Team Mix On The Diamond Today.” Around that time, the Klan, or Klu Klux Klan, was trying to give itself a new image, one that was not as racist and hurtful to African-Americans. So, a team of Klan members decided to play the Wichita Colored Western League’s Monrovians.

The Monrovians ended up winning 10–8, and there were no major incidents related to racial tension. I think this is a super interesting artifact. It is only a newspaper clipping, yet it tells us so much about history!

Another significant artifact in the museum is a signed baseball. This is not just any baseball; it is baseball signed on one side by Robinson, Jim Gilliam, Joe Black, and Roy Campanella (African-American MLB players) and on the other side by Ty Cobb, a white player and arguably one of the greatest of all time.

The baseball belonged to a man named John S. Moore. Moore had been Robinson’s friend while he was in the army. When Robinson went to the majors, Moore kept in touch with him and went to see him play in Chicago.

In Chicago, Robinson helped Moore get the signatures of Gilliam, Black, and Campanella, and then during the game, the announcer said that Cobb himself was in the stands. Moore made a point of going to get Cobb’s autograph too. No one knows in which order the baseball was signed, but the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum believes this is the order.

Jackie Robinson in his Kansas City Monarchs uniform

What makes this collection of signatures interesting is that Cobb and Robinson were often compared to each other as players. Both were thought to be among the best players of their eras. Another interesting point is the fact that Cobb signed a ball with African-American players’ signatures on it, especially because Cobb is historically remembered as a racist.

Moore’s daughters now own this baseball; they want to keep it in the family. They do not to want to sell it, but it is on loan to the museum. Regardless, this ball is amazingly valuable, according to Dr. Raymond Doswell, vice president of curatorial services at the museum, and is worth about $15,000.

Dr. Doswell gave my dad and me a fantastic tour of the museum and told me about these amazing artifacts. He also shared some fun facts with me. Did you know that night games came to the Negro leagues in 1930, five years before major league teams had lighting? Dr. Doswell wants people who visit the museum to leave remembering that sports and history are closely intertwined.

According to Dr. Doswell, retired MLB commissioner Fay Vincent wrote in his book about how it was good that there were Negro leagues but that it was a tragedy for our country. It was, and that is why it is important to honor these leagues and players. The museum takes great pride in its role as educator, teaching people about the Negro leagues and players.

My visit to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum was very thought-provoking. If you're ever in Kansas City, I suggest that you go.

Photos: Charlie Riedel/AP (museum), Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images (team), AP Photo (Robinson)