Legendary Boxer and Sports Icon Muhammad Ali Dies at 74

If Muhammad Ali was in his time the most famous person in the world, it was as much a tribute to his talent for provocation as to his boxing. He was a glorious athlete, of course, his white-tasseled feet a blur to match his whizzing fists. But his legacy as a global personality owes more to that glint in his eye, to his capacity for tomfoolery, to his playfulness. He was a born prankster, giddy in his eagerness to surprise, and the world won’t soon forget his insistence upon fun.

Fighting in the far corners of the earth, when that was still done, he was our most popular ambassador for a quarter of a century, advancing the American doctrine of self-satisfaction. His practiced malarkey—the doggerel of doom, the ritual belittlement—didn’t so much enliven his sport as it created a whole new form of entertainment. Really, there was boxing, and there was Ali—who died late Friday at the age of 74—and everybody knew the difference. In time his artful application of nonsense would be revealed as a facade, covering a deeper mission of empowerment. But watching him emerge in Zaire, Manila or even Cleveland was to witness a one-man comic relief effort. He was a a traveling circus unto himself, the highest embodiment of self-confidence.

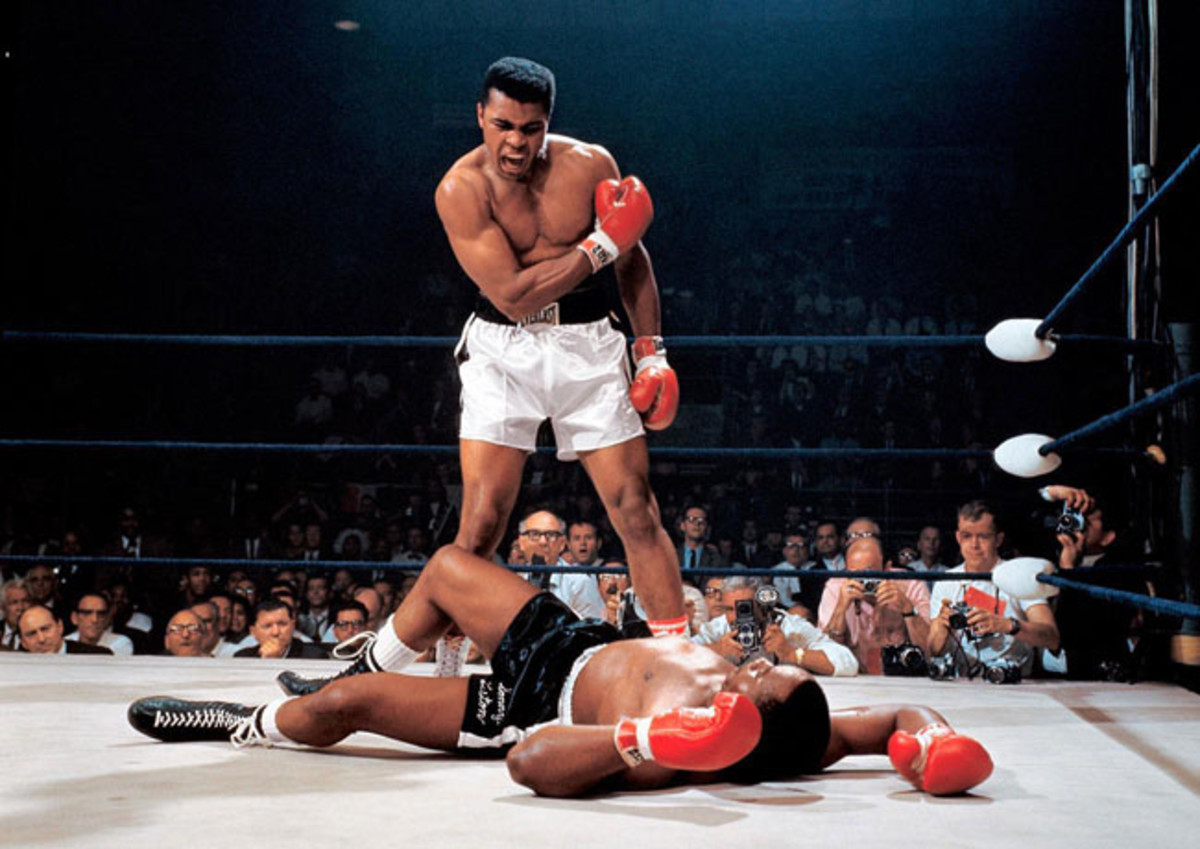

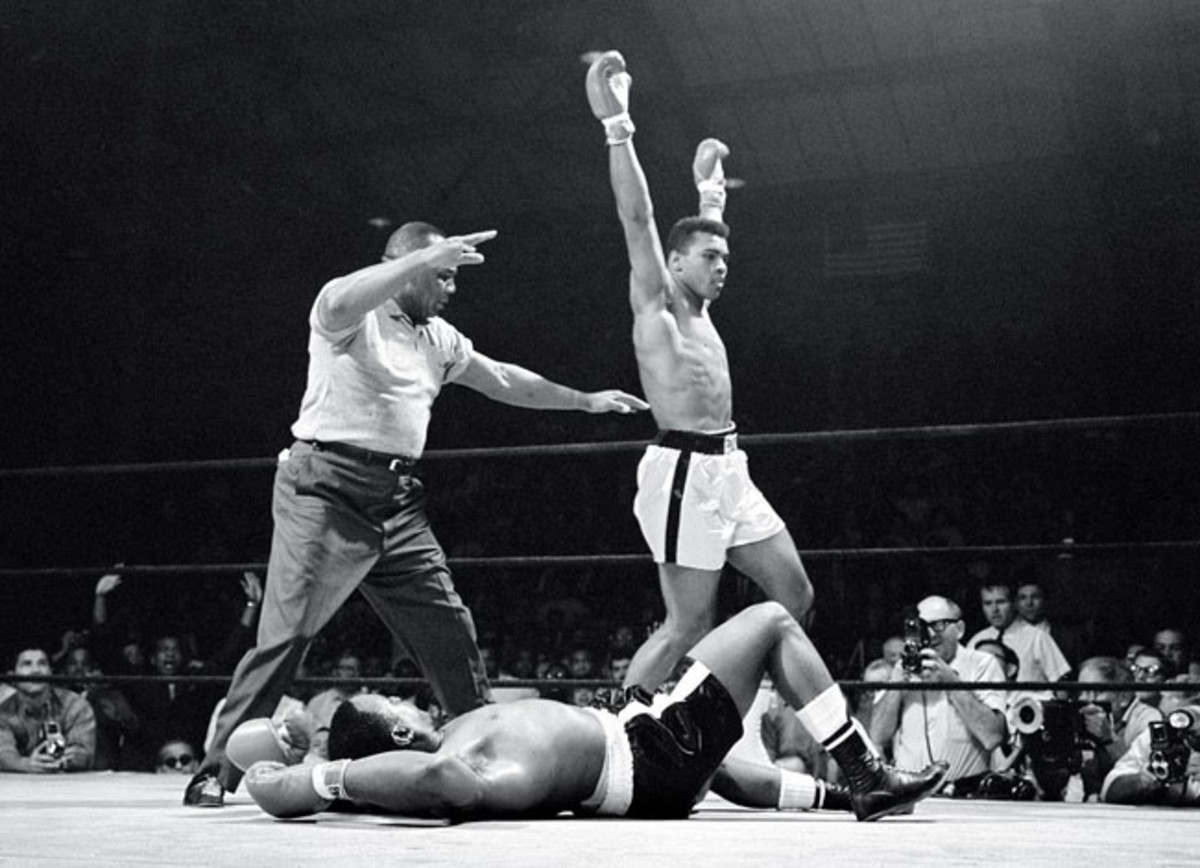

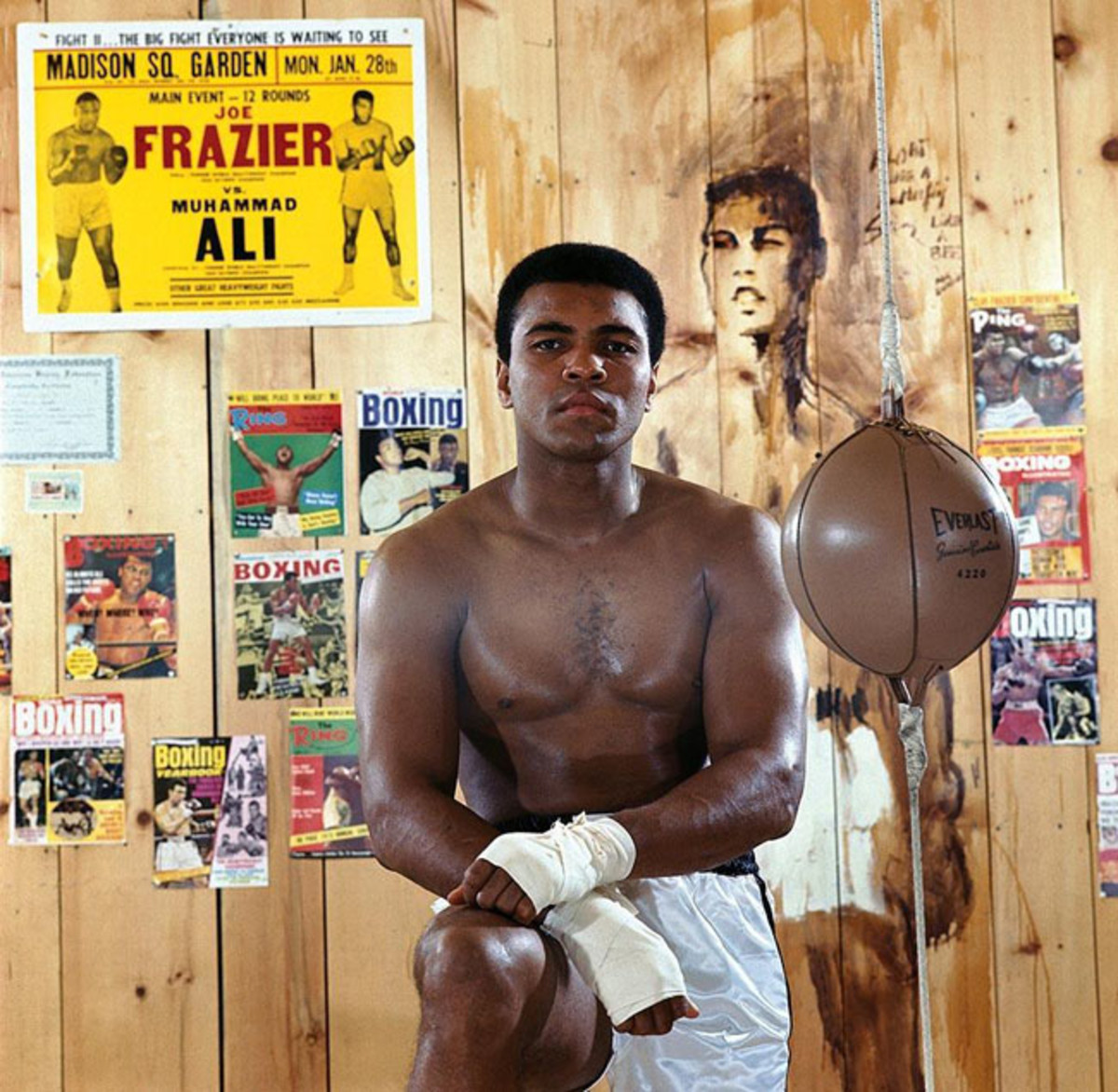

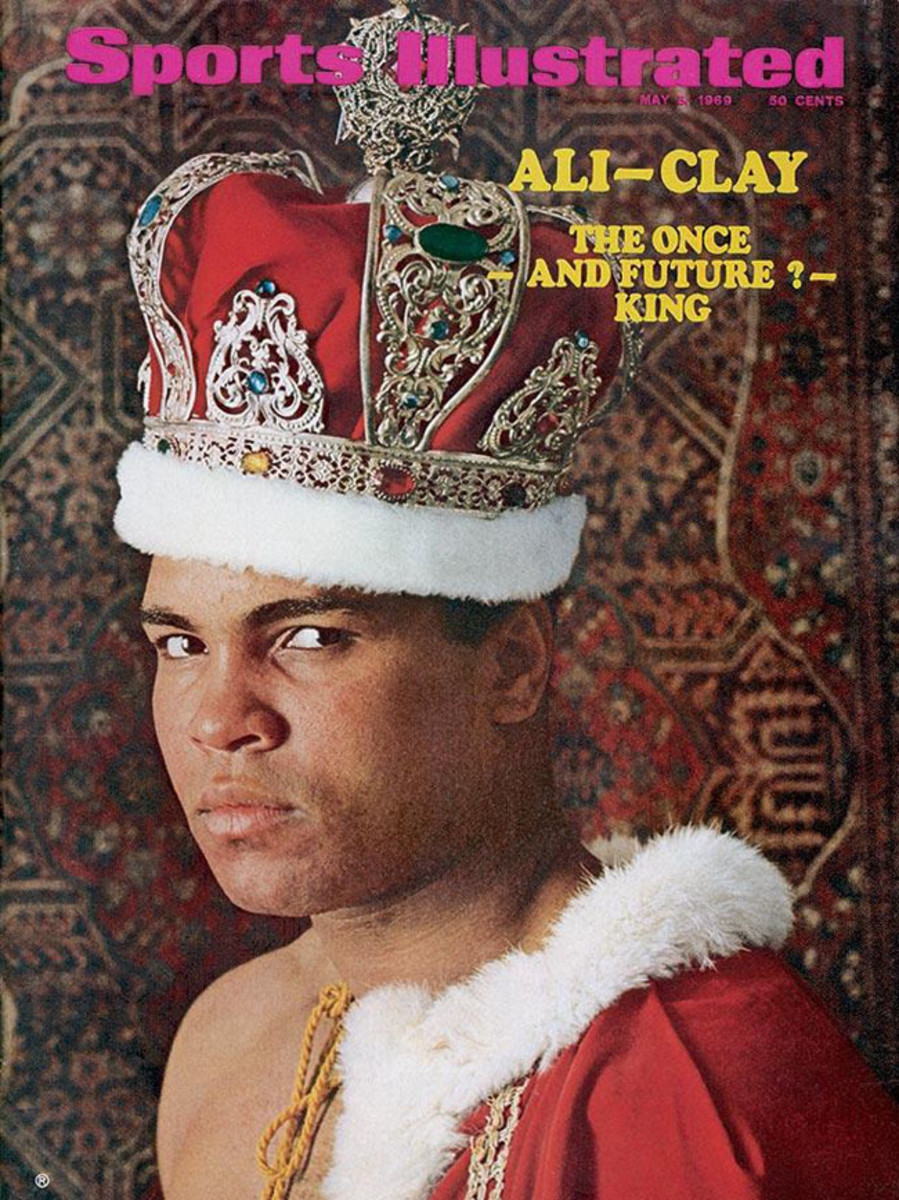

It must be said, first of all, that Ali was, just as he used to boast, the Greatest of All Time (which in later years became the typically playful acronym—GOAT—that branded his projects). He won the heavyweight title three times, in an era of ungodly competition. Neither Joe Louis nor Rocky Marciano faced so many dangerous fighters still in their primes. Ali’s trilogy with Joe Frazier provided enough drama in the first bout alone to be deemed mythic. Then there was the fight with George Foreman, when Ali, many thought, was being sent to his doom but instead invented an almost comical escape, the rope-a-dope. Not to mention bouts with Sonny Liston, Ken Norton, Earnie Shavers, killers all. In his heyday, at least, Ali fought not for survival but for his own entertainment. He presented his ring art as a kind of jazz, fully improvisational, performed to the whimsical score in his head.

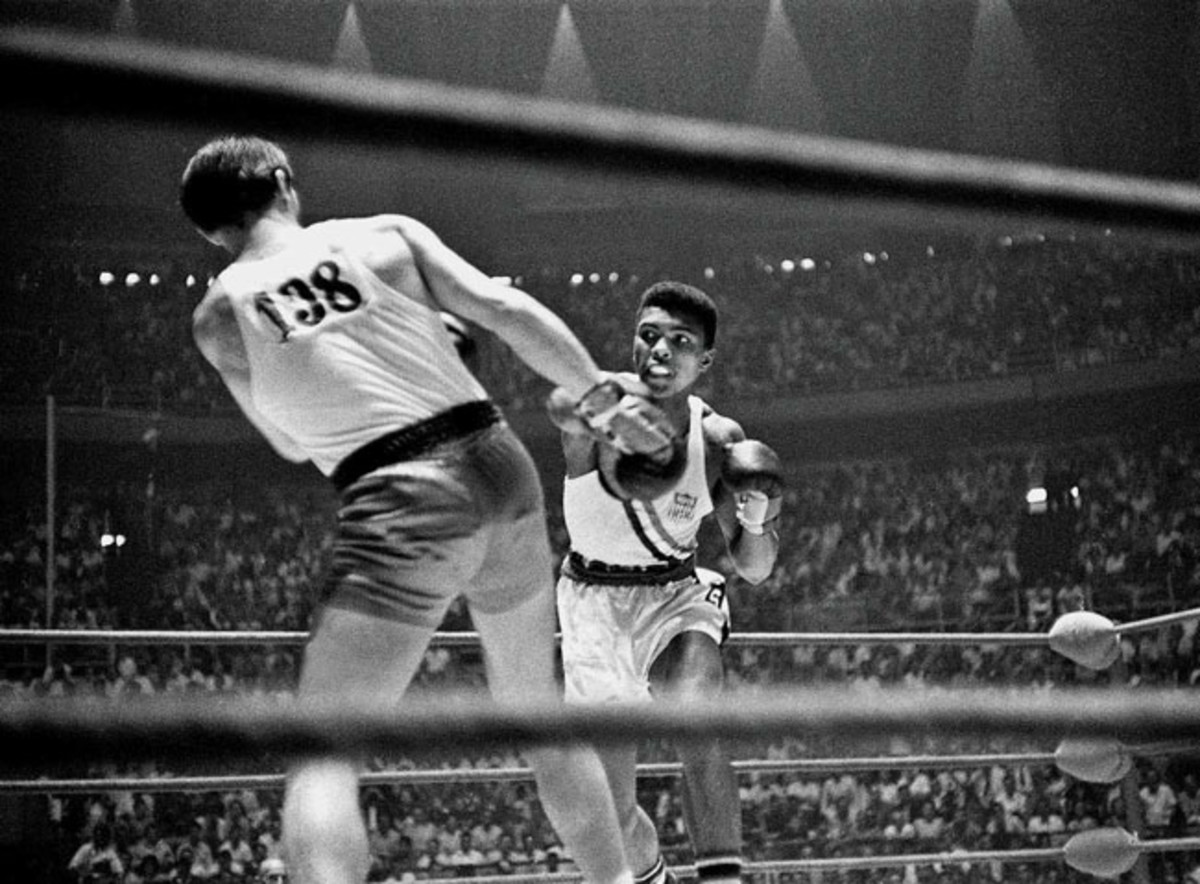

His career stretched from the 1960 Rome Olympics, at which he won a gold medal, to a sad and unnecessary fight in 1981, an ugly loss to Trevor Berbick on an island outpost. It was a period of high achievement and sometimes sad surprise, played out across continents. Till then no athlete, certainly no black athlete, dared be so brazen, so bombastic, so certain in his appeal, so independent of tradition. Ali promoted himself unashamedly, scorning the pitiful opposition, predicting the exact round of their departure and generally elevating his own stature to that of god. And then he adorned his own grace in the ring—so big and so fast!—with unusual and maddening filigrees. Can you imagine, in such a deadly game, a fighter who pauses for a pugilistic break dance, a shuffle in which his white shoes skim the canvas? For that matter: white shoes?

It helped that Ali came of age in a time, and in a country, when such things as race, religion and politics were being explored more openly than ever. Although most of the tension he liked to create—whether through cruelty to opponents or just unspeakable flamboyance—could be cut with that puckishness, he did have a serious side. Switching religions at age 22, converting to the Nation of Islam just as he was coming to real prominence, was not the move to make if marketing was your game, not while the black man was still being advised to follow the get-along mode. And risking jail, suffering exile, for an antiwar stand in 1966 was not something done out of playfulness. He had his convictions and he stuck to them, even if it meant paying a tremendous price.

But it was just that strange mix of traits, courage and an equally adamant foolishness that turned him into an icon. Before a fight he might advise, “If Ali says a mosquito can pull a plow, don’t ask how. Hitch him up!” Then, as he dominated another opponent, he might lean over the ropes and affect an exaggerated yawn. Or, on very different nights, he might find himself teetering on the fighter’s abyss of surrender, what he once called “the near room,” where snakes screamed and alligators played trombones. He never once went in.

Later in his life, when the man who could float like a butterfly was palsied, when that once indomitable mouth was mostly silenced, he became not just famous but beloved. It was a horrible irony to see such physical elegance stiffened by Parkinson’s, but like everything else that came along for Ali, his impairment was one more opportunity to prove his greatness, perhaps even enlarge his already considerable constituency. For his last 20 years, the Ali shuffle was indeed his only form of locomotion, and it was painful to see his jazz become fugue. But he was uncomplaining, dignified, unmindful even of any infirmity, and he kept about his proselytizing, which, more than anything, meant sharing his peculiar mysticism. He’d still stoop to produce a quarter from behind a child’s ear, but now he’d explain the trickery. No need to hoodwink anybody anymore. Life was too short.

Born Cassius Clay in 1942 in a middle-class neighborhood in that Louisville, Kentucky—his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr., was a painter, dabbling in murals but mostly laboring at billboards and signs; his mother, Odessa, a maid—Cassius Jr. was one of those children a parent might term a mixed blessing. High-spirited even then, he liked to tie a string to the bedroom curtain and move it back and forth until his parents sprang from their beds, fully spooked.

His boxing career was born in tears, not laughs, though, when his red-and-white Schwinn was stolen from outside the Columbia Auditorium. (The 12-year-old Cassius and a friend were at the Louisville Home Show, roaming the booths to score free popcorn.) He sought out the nearest policeman, who happened to be coaching young boxers in the auditorium’s basement. A crying Cassius told Joe Martin he intended to whip whoever took his bike, and Martin said if this was so, maybe he ought to begin his study in the whipping arts right there.

Cassius turned out to be a hardworking pupil, though hardly a prodigy. His talent emerged in time, and he found the sport to be just the thing for a kid of growing vanity, never mind ambition. Those first amateur fights were often televised locally, and Cassius discovered he liked the attention. As a 12-year-old he was stirring the pot, trash-talking behind his jabs. The crowds went wild. And newspapers! They’d write anything he said, as it turned out. “This guy must be done,” he told the Courier-Journal, in what might have been his very first rhyme. “I’ll stop him in one.”

The spotlight, in whatever form, was not something Cassius ever chose to avoid. His was just one of those childlike appetites. A former amateur boxing official, Bob Surkein, told Ali biographer Thomas Hauser of an out-of-town tournament in which the teenaged Cassius won by a first-round knockout. The next day, trying to buy a newspaper in the hotel lobby, Surkein realized that all the sports sections were missing. Suspecting Clay, he barged into his room and, sure enough, he was carefully clipping his picture from each of the pilfered sports sections. Still, Surkein remembered, the arrogance was never off-putting because it was always suffused with such youthful innocence. Walking with Surkein on the Atlantic City boardwalk, Clay offered in awe: “Man, that’s the biggest damn lake I’ve ever seen."

Clay won the National Golden Gloves (during which he showcased his shuffle) and made the Olympic team (having advised journalist Dick Schaap earlier that summer that he’d “be the greatest of all time”), winning his gold as a light heavyweight.

His early professional career was fortuitous, in that he was backed by a group of 11 Louisville businessmen, who were out more for a lark than a buck. Additionally, Clay was exposed to instructive influences, including the equally loquacious former light heavyweight champ Archie Moore, who in late 1960 briefly hosted the young fighter in his training camp, and the Miami trainer Angelo Dundee, who tolerated his buffoonery and even encouraged his unorthodoxy in the ring, dangling arms and all. Perhaps nothing had a bigger impact, though, than a chance meeting with professional wrestler Gorgeous George. Clay was awestruck by the man’s rant. Later Gorgeous took Clay (himself known as Gaseous Cassius at the time) aside and instructed him thus: “Keep on bragging, keep on sassing and always be outrageous.”

Until 1964, Clay’s reputation was based more on poetry and predictions than performance. But it was the calculating application of this outrageousness that finally got him his first championship. Would the fearsome Sonny Liston, the Bear, ever have bothered with such a pest if Clay hadn’t rolled up on his Denver house at 3 a.m. in a 30-passenger bus painted with the inscriptions, world’s most colorful fighter and liston must go in eight? Liston just stood there in his pajamas, flabbergasted. Later he agreed to fight the upstart.

That event was essentially a case study in hysteria, all of it Clay’s, so much so that rumors were still flying at ringside at Miami Beach’s Convention Hall before the fight that Clay was on his way to the airport, perhaps headed to South America. Fear certainly would have been appropriate: Liston was a known destroyer, and Clay, clever as he might have been, was no better than a 7-to-1 underdog. His poetic prediction—Who would have thought, when they came to the fight/They’d see the launching of a human satellite—seemed the worst kind of whistling past the graveyard. And for anyone looking for proof of his fragile self-confidence, there was the unsettling psychodrama at the weigh-in, where, eyes popping and arms waving, Clay produced such an alarmingly high blood-pressure reading that the commission doctor nearly disqualified him.

Clay had no such uncertainty, of course. Except for a moment before the fifth round when he nearly refused to go on—his eyes were burning from some substance, possibly on Liston’s gloves and skin—he calmly dismantled the bigger man, leaning backward out of harm’s way, bloodying Liston until he finally quit on his stool before the start of the seventh round. But again, the fight was only a preamble to the real performance, which featured Clay proclaiming his greatness, as well as his prettiness. “I shook up the world,” he hollered. “I’m a bad man.”

In films of the fight you can see him looking toward press row, pointing his gloved hand at the disbelievers, one by one. He was saying, “I fooled you, I fooled you, I fooled you. ...”

Clay may have made believers in that fight, but he had yet to make followers. He could never understand why everybody didn’t board his personal fun bus. “Why ain’t you taking notice?” he’d ask when things got too serious. “Why ain’t you laughing?” But it wasn’t always laughs. Almost immediately after the Liston fight, the Baptist-born Clay announced he had yielded to his growing fascination with the Nation of Islam’s teachings and become a Muslim, taking the name of Muhammad Ali, a move that could only have a polarizing effect.

For a while Muhammad Ali was every bit as much fun as Cassius Clay had been. The Vietnam War changed all that. Ali, who was dyslexic and a poor reader, had tested well below the mental competency requirements for the military draft and been classified 1-Y. But when he was reclassified and slated for induction, Ali explained his objections, not just on religious grounds but also racial. Bob Arum, who got his start as a promoter with Ali in 1965, was horrified. “Mortified, actually,” he said. “You have to understand, this was light-years before any protest.”

Ali had already stirred up closet resentments, on account of his race and his religion. But here was an objection—the man was unpatriotic!—that could be freely expressed by all his detractors. “We were pariahs,” said Arum.

At first Ali was forced to defend his title outside the country, returning from bouts in Toronto and London and Frankfurt to make tentative stands in Houston. But even by 1967 the logic or nobility of his objection to the war remained unpopular. Not to mention illegal. He was sentenced to five years in prison for refusing the draft (a decision overturned by the Supreme Court four years later) and, though appeals kept him free, was essentially drummed from boxing for the next 3 1/2 years when the New York commission stripped his title. The exile robbed him of his prime but deepened his significance as a political icon. The war would not long remain popular, or even viable; Ali, as the times caught up to his convictions, was restored as a man of substance, possibly even history.

The exile also sharpened his showmanship, offering him the opportunity (the need actually; he was soon out of money) to appear on Broadway and on game shows and to speak on college campuses. But by the time he was able to edge back into boxing (Atlanta, which had no commission, offered him his first bout back, in October 1970 against Jerry Quarry; New York and the rest of the world followed suit), he was hardly the prancing pugilist he had been at the age of 25.

If he had been interesting in exile, he now had the chance to be truly mythic in his return to the sport. He was now doubly saddled, with the baggage of his unpopular politics and the frightening reality of a comeback at age 28, when the heavyweight division had become populated by the likes of Joe Frazier, George Foreman and Ken Norton. Foregoing a tune-up, Ali fought contenders Quarry and Oscar Bonavena within six weeks, stopping both and demanding a shot at his old title by 1971.

That bout with Frazier, whose brutish left hook had left a trail of victims on his way to Ali’s stripped title, was immediately billed as the Fight of the Century, two undefeated heavyweights with equally valid claims to the championship. But it was even more than that. They offered contrast at every level: It was Ali’s boxing versus Frazier’s punching power; Ali’s showmanship versus Frazier’s stoicism; Ali’s social activism versus Frazier’s political conservatism. “The whole country was choosing up sides,” said Larry Merchant, then a columnist at the Philadelphia Daily News. “It was the red states versus the blue states.”

Merchant, for more than 30 years an HBO boxing analyst, has not seen such anticipation at ringside since. It was probably enough that two big men of equal skill and determination were fighting for a championship. But Ali, “a litmus test for where you stood on about 100 issues,” says Merchant, added an element of social tension to the proceedings, just by his presence. Throw in his worldwide celebrity, and the Fight of the Century became a cultural event as well. Burt Lancaster was doing the color commentary for the closed-circuit broadcast. Frank Sinatra was snapping pictures for Life magazine. Movie stars attended. Politicians.

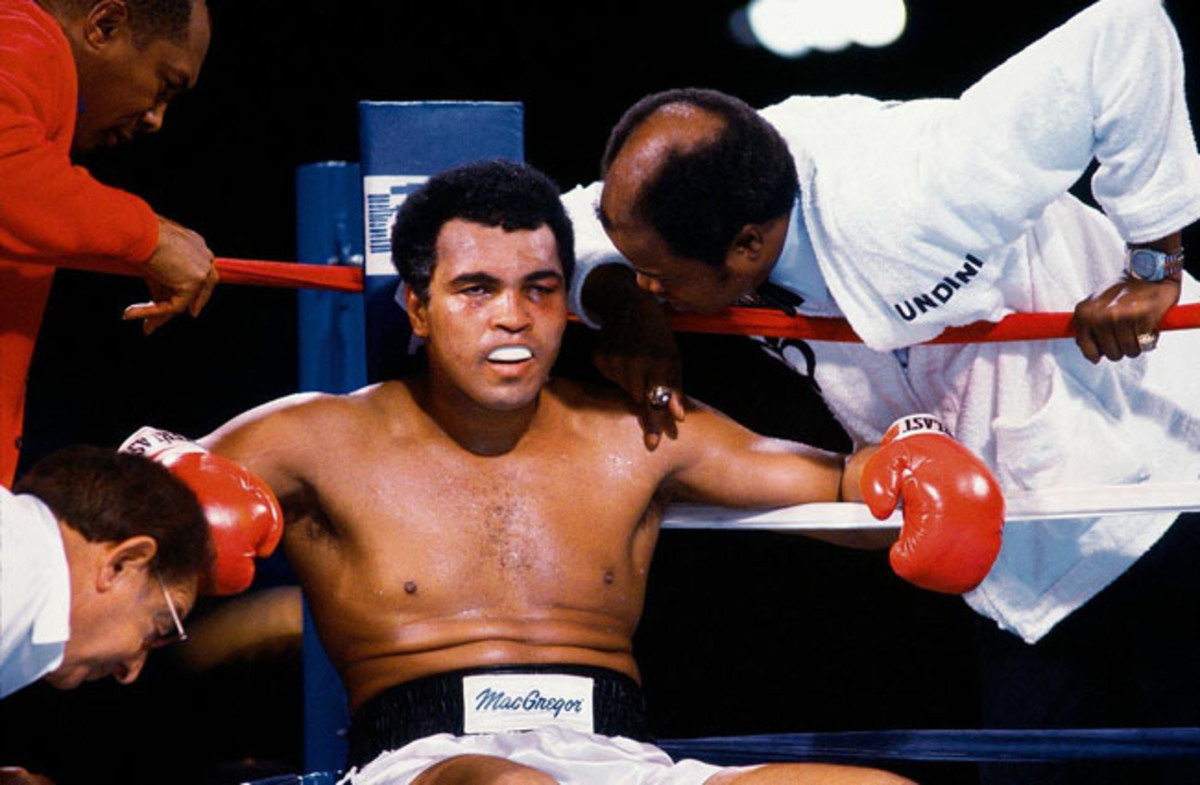

Everybody who was in Madison Square Garden on the night of March 8, 1971, still talks about the turbo whine of excitement that preceded the bell, a visceral roar. Ali fought comparatively flat-footed, his featherweight footwork replaced with resolve, and with an iron jaw. Though Frazier’s face would soon take on the aspects of a patchwork quilt, it was Ali’s swollen jaw that was the most telling evidence in Frazier’s win by decision. A left hook in the 11th nearly sent Ali into the celebrities’ laps. Another in the 15th dropped him.

The fact that Frazier, the winner, spent three weeks in the hospital and that Ali, the loser, was soon making the talk show rounds did not really alter the new heavyweight landscape. What did were losses by the principals before a rematch could be arranged. Frazier was nearly decapitated by the sullen and forbidding George Foreman in January 1973, and Ali decisioned by Ken Norton two months later.

These circumstances did not afford the same drama to Ali-Frazier II, again in the Garden (which Ali won, fighting more cleverly than bravely this time), but did create immense anticipation for Ali’s next title charge, against Foreman in Zaire on Oct. 30, 1974. By now Ali, though still mightily poetic outside the ring, was no longer an artist within. At 32, fully a decade after he first won the title from Liston, he had to rely on his resolve and resiliency—sadly, his jaw—to get through fights now. This would hardly do against a 25-year-old knockout machine like Foreman. Survival was about all that could be hoped for.

Beyond the bout, the whole occasion became terribly important to Ali; seeing Africa for the first time was truly an eye-opener for him. The trip was the basis for his development as a world citizen, when he first recognized his ability to gather different cultures about him. But he was a natural that way. It wasn’t long before he landed that the crowds were chanting, “Ali, bomaye!” (Ali, kill him!)

Ali seemed incapable of killing Foreman, though, and indeed appeared in mortal peril himself. Yet he invented a stunning strategy, which demanded he accept Foreman’s heavy hands as he sagged back into the ropes. Later christened rope-a-dope, the game-plan at first appeared suicidal but then, as Foreman grew arm weary, brilliant. Although Ali suffered the kind of punishment that can take years to fully manifest itself, the tactic did result in an amazing victory when he took Foreman out in the eighth round.

This set up the Thrilla in Manila on Oct. 1, 1975, the last fight in the Ali-Frazier trilogy, the one that damaged both men beyond repair. It was another brutal meeting, in which each fighter’s skills were revealed as thin veneers for a horrifying toughness beneath; each was willing to accept near-fatal blows in the hope of winning a terrifying war of attrition. Ali, who later recalled the bout as “the closest thing to death I know,” prevailed when Frazier’s trainer Eddie Futch refused to let him come out for the 15th round.

Ali should have retired; the third Frazier fight really was the capstone of his career. But he fought on, nearly losing again to Norton, splitting matches with Leon Spinks, losing to former sparring partner Larry Holmes and, finally, a month before his 40th birthday, to Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas. Each of these largely unnecessary fights, while leaving his legacy intact (so forgiving is memory), deepened the devastation of pugilistic parkinsonism, an artifact of his competitive drive.

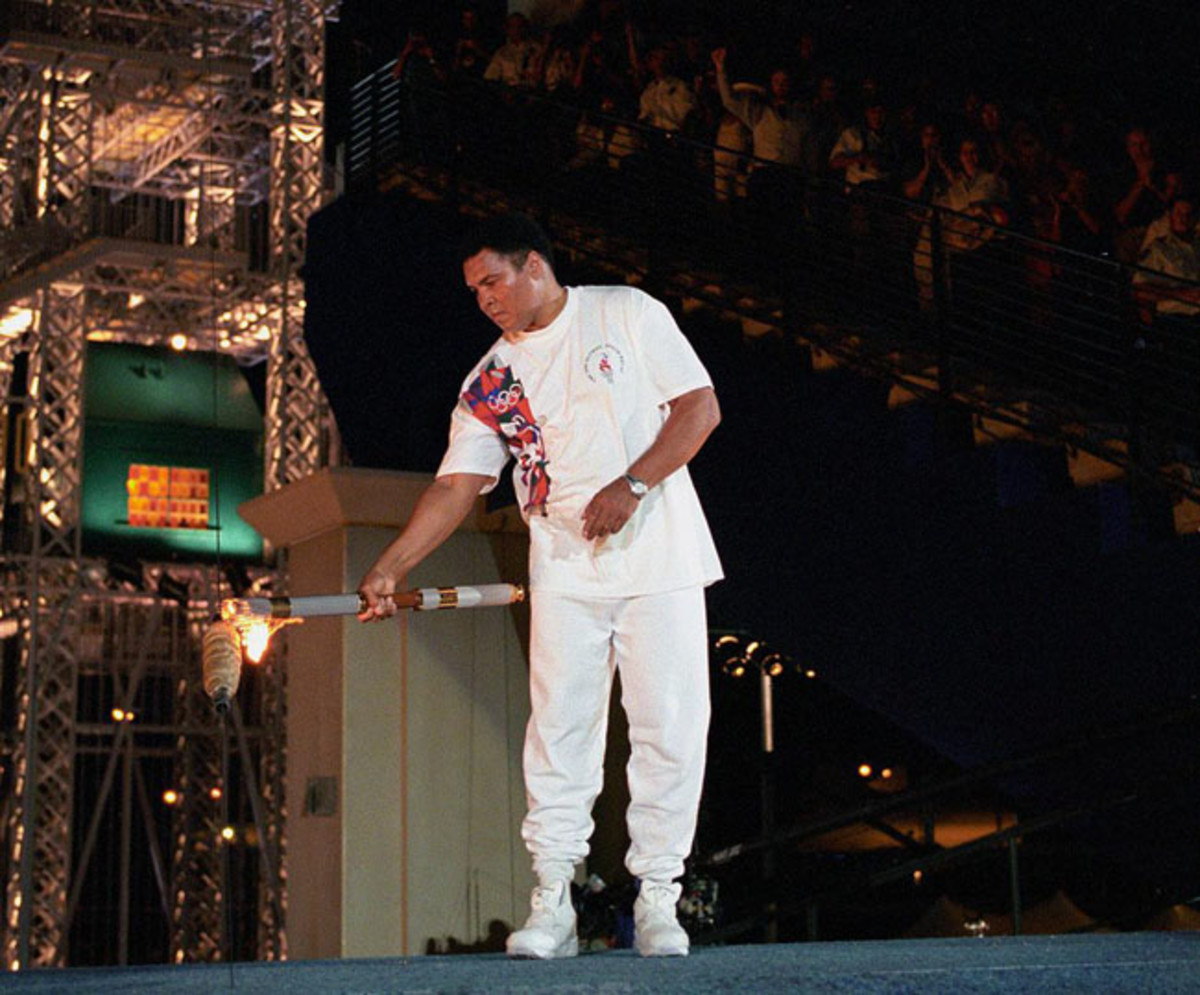

The disease, even if it was a predictable result of so much punishment in the ring, was a cruel coda to a career built on the beautification of an ugly sport. Ali, properly medicated, could still occasionally muster that old playfulness, produce an on-cue shuffle, recall a rhyme. But his public persona became, mostly, a steady and horrible deterioration. The disease robbed him of his trademark mugging; his face was rigid and expressionless. And his physical magnificence—indeed, the ability to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee—was now betrayed in the worst possible way. He was unsteady, he trembled violently, he moved slowly. In 1996, when Ali was the surprise choice to light the Olympic flame, the full extent of his disability became apparent to a world audience. Making no concession to the disease, Ali painstakingly climbed the stadium steps and with terribly shaking hands held the torch aloft and waved it to the crowd.

Yet Ali was never bitter, nor did he recognize irony, or even tragedy, in the loss of gifts that had been so central to his being. Instead, he bent himself to a new purpose, which was simply humanizing the rest of the world. A born ambassador, he now shrewdly used his infirmity in delivering his message; formerly fierce and admired, he was now destroyed and beloved. “They thought I was Superman,” he said in 1988. “Now they can say, ‘He’s human, like us.’ ”

His retirement was devoted to a variety of enterprises, most of them noble but some less so, the odd celebrity-for-hire gigs that could be uncomfortable to watch. At one point he was traveling as many as 275 days a year, making as much as $200,000 for a public appearance. His itineraries were ferocious as he accepted honorary degrees, delivered letters on world peace, testified before Congress on Parkinson’s research and appeared (in successive years) at both the Indy 500 and in Kabul. He became central to legislation in his sport when Senator John McCain introduced the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act. Passed in 2000, it protects fighters from predatory managers and one-sided contracts.

At the same time he was able to relax in his celebrity, to enjoy a life of missionary work and statesmanship—even to accept the love of enemies, converted by that persistent pursuit of fun. Foreman, who had been emotionally eviscerated by the loss to Ali, and who said he spent much of the following decade “hating that guy,” later found himself paired with him on a small-scale old-timers’ tour. In a reflex that only Ali could inspire, Foreman discovered himself adjusting the man’s coat before the appearance. Ali glanced back, surprised. “You really are pretty,” Foreman said, at long last laughing.

In later years, for all the appearances he made, Ali was mostly mute, perhaps simply resigned to accepting the machinations of others. Behind this stony and implacable exterior, his glee or his ambition or even his easy grace was not immediately apparent. Though, really, for anyone who was alive during Ali’s extravagantly orchestrated life of hurly-burly—we really did have to laugh, didn’t we?—the spirit beneath was never in doubt. You could always see that twinkle in his eye.

Photos: Neil Leifer, except Jerry Cooke (Olympics action), Johan Iacono (final match), Peter Read Miller (Olympic torch)