How Soccer Players Are Getting Smarter On the Field With Brain-Training Video Games

by Tom Taylor

A couple of times a week Calvin Stengs steers his blue spaceship through empty space, avoiding swarming red enemy craft, and fires a glowing yellow hexagon at a fluorescent green panel. On weekends, the 18-year-old strides across a green field, dodging opposition players, and shoots a white ball at the rectangular mouth of a soccer goal. Stengs is a striker at AZ Alkmaar, a Dutch soccer team that plays in the country’s top division, the Eredvisie. Soccer is his career, but space captain is more than just a hobby.

Video games might be the future of soccer. But that doesn’t mean EA’s FIFA series or any of the computer programs fueling eSports. The game Stengs plays—IntelliGym—isn’t supposed to be fun, or to look much like real life, but to train his cognitive skills: how quickly he can anticipate plays, how well he can recognize movement patterns and keep track of multiple players at the same time, how quickly he can mentally switch from offense to defense, or vice versa, and how much memory space his brain has to process all of that.

More than two decades ago, Daniel Gopher, a former Israeli Air Force psychologist, found that a video game called Space Fortress actively improved cognitive skills in pilots. (The game had originally been developed by psychologists at the University of Illinois to investigate skill acquisition.) A study Gopher published in the journal Human Factors in 1994 showed a significant improvement in the flight performance scores of 33 Israeli Air Force cadets.

Danny Dankner was in flight school back then, but wasn’t part of the study. But years later, when he finally picked up the controls to Space Fortress, he saw the game’s potential. In 2001, Dankner co-founded Applied Cognitive Engineering, the company that makes IntelliGym, and set his sights on first basketball and hockey. “Sport, from a cognitive standpoint, is very similar to flight,” Dankner says. “If you think about competitive athletes, and particularly team sports, you have a very complex environment.” Gopher, and professor emeritus at Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, now supervises ACE’s research.

In sports, smaller teams who can’t simply bankroll the most valuable rosters have to find their edges elsewhere. Unlike the powerhouses of European soccer—teams like Manchester United, Barcelona, and Real Madrid—Dutch clubs like PSV Eindhoven and AZ Alkmaar have little to tempt the most sought after players. Both PSV and AZ have won the Netherlands’ top division, the Eredivisie, in the last decade, but neither has reached a major European final since 1988.

These are the Oakland A’s of soccer. “A relative low budget means you are forced to be smart to stay competitive,” explains Luc van Agt, a sports physiologist at PSV. The Moneyball analogy is more than skin deep; A’s executive VP of baseball operations Billy Beane signed on as an advisor to AZ two years ago.

In 2015, ACE received a $2.2 million grant from the European Union to develop a soccer specific version of IntelliGym. PSV, AZ, and eight other European teams signed on to help ACE determine what cognitive skills are required for soccer.

When the new system was up and running, PSV and AZ rolled it out to their junior teams. “The academy is the laboratory of the club,” says Marijn Beuker, head of performance and development at AZ. Younger players are also more teachable than their more established elders. “The most tactical phase to train the players is between 14 and 17,” van Agt says.

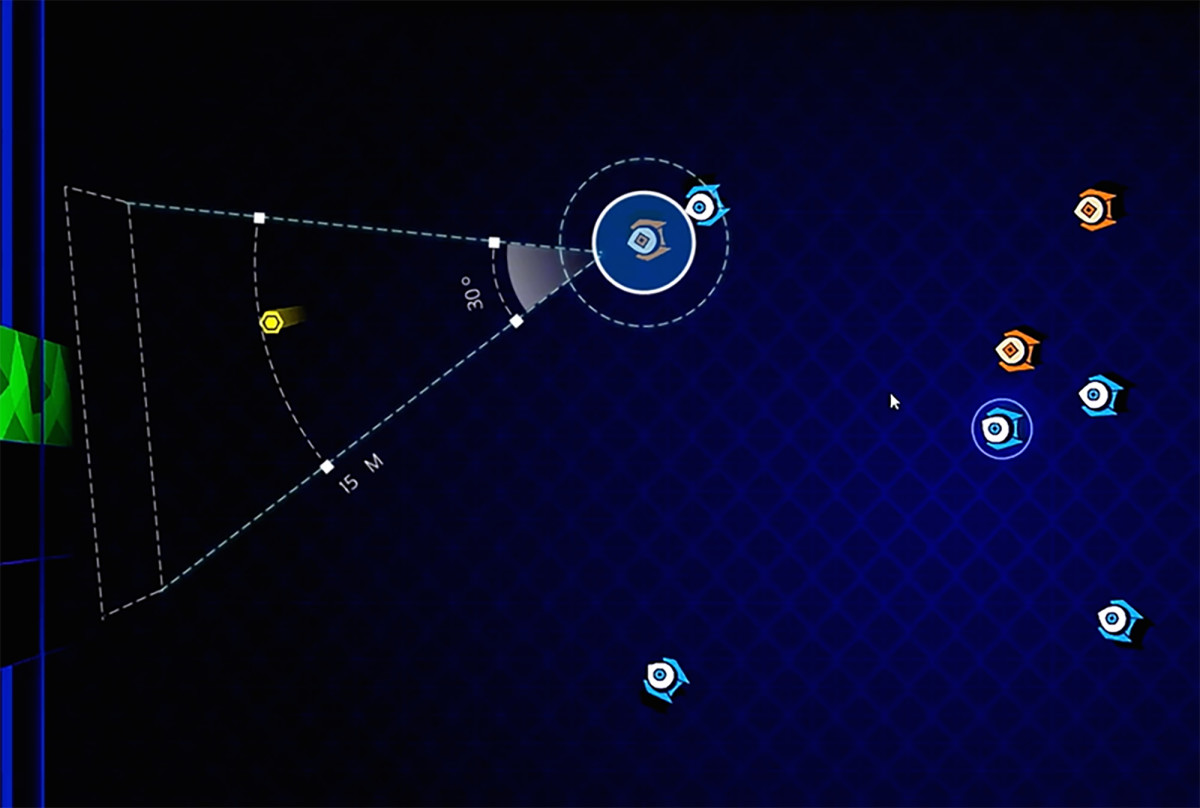

The Football IntelliGym looks a little like a soccer game with the players switched out with blue and red spaceships. A user pilots one of those ships around a rectangular arena, dragging teammates into position, and passing and shooting a yellow hexagon. Players are challenged to track multiple objects and anticipate movement. And as the user succeeds or fails, the drills adapt.

Beuker believes that smarter players will free players from rigid formations and make soccer more exciting. “Tactics basically means that I tell you what to do,” he says. “The problem is that that’s not football. In general, that’s not how people get creative.”

An analysis by Geert Savelsbergh of the department of human movement sciences at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, funded by ACE and the EU, found a significant improvement in the on-field performance of youth players at PSV and AZ last year. Performance was rated by recording, and then reviewing, video of short games played over a small area. Players trained with IntelliGym were seen to improve by an average of 35% compared to 5% for a control group.

“We saw progress in the attacking part and the switching to transition play, the switching to attacking,” Beuker says. However, Jurrit Sanders, a sports scientist who runs the IntelliGym program at PSV, cautions that understanding the reason for performance changes can be tricky. “It’s very difficult to say whether a player improved because of IntelliGym or because of something else,” he says.

The real test will come in the Eredivisie. Stengs might be the first IntelliGym player to graduate to AZ’s senior team, but others will soon follow him.

(Photos courtesy of Intelligym)